-

MY FIRST LIONESS Two slide projections and a puzzle, Tiroler Künstlerschaft, Innsbruck, 2013. Photos: WEST. Fotostudio

Opening speech

Ingeborg Erhard

My First Lioness, My Fifth Lioness, My First Leopard … Tatiana Lecomte has taken picture captions like these from old books published in the first four decades of the 20th century and combined them with, among other things, slides from the estate of a person she knows nothing about. It is presumably private documentation of a journey to Africa that most likely took place in the 1960s. The artist presents the new work My First Lioness, which also provides the title for her solo presentation in the Neue Galerie, as a double projection on two levels: as original material arranged simply in order, and as a kind of picture essay. For this, Tatiana Lecomte repro-photographs the found slides, then selects sections to zoom in on. These images are then supplemented by other materials such as reproductions from books that she has found during her research into the topic, or pictures from her own archive. The text level is also “borrowed”. All the subtitles used in the slide installation have been re-photographed from a range of sources and thus retain their original typography. Associations with silent films or old photo albums are fully intended by the artist, not only due to her predominant use of black and white.

Apparently, images of the mysterious Black Continent have not changed for decades: e.g. bare-bosomed black women carrying loads on their heads and/or with children strapped to their bodies, or armed white big-game hunters/researchers touching their quarry, sitting or kneeling on the dead animals. The researcher, whether male or female, is portrayed as a conquerer who classifies, archives, takes possession of, robs, interprets, and misuses for his own purposes the people, animals and landscape of Africa. Generally speaking, people and animals are shown with no differentiation as a “prize”. Parallels between hunting and photography (shooting) are quite intentional. The starting point for this work is Leni Riefenstahl’s gesture among the Nuba from the photo series Leni. This image also appears in My First Lioness.

Tatiana Lecomte is concerned with the images themselves. She does not wish to make any kind of moral comment but asks how such images – in the recipients as well – are produced and reproduced. Is what we see here confirmation of how we have imagined Africa to be for generations?

Roswitha Muttenthaler and Regina Wonisch write in “Gesten des Zeigens. Zur Repräsentation von Gender und Race in Ausstellungen”[1] (Gestures of Pointing. The Representation of Gender and Race in Exhibitions) : “Museums, therefore, not only create images corresponding to our social norms; they also examine things that are concealed. They not only represent the visible, but also the things we seek to withhold from public discourse and perception, and thus exclude. […] In the process they have produced mechanisms of inclusion and exclusion based on dichotomic opposites, in accordance with the ideas of modernity. Concepts of identity tend to be founded on the construction of difference, whereby identity is defined in a distancing from the other, which is generally conceived as negation. Thus, for example, sexual or ethnical identities are characterized by processes of negative differentiation in the field of visibility: Whites need Blacks in order to define themselves as white, masculinity needs femininity in order to construct itself as masculine, etc. Specific social groups or cultures have been either excluded from the practices of representation or marked as others. […] Before the background of collective identity politics, the field of vision became a contested scenario, a matter of vehemently and enduringly establishing unstable norms.” Tatiana Lecomte is aware of these mechanisms. She assembles associative sequences of images that appear, on the one hand, to confirm the recipients’ traditional viewing habits; on the other hand, they are capable of shaking them as a result of interruptions and irritations. She opens the narrative to the ambiguities that can often be found between the images.

Positions at El-Alamein is a montage in Tatiana Lecomte’s oeuvre that anticipates My First Lioness. It is also a slide installation, reminiscent of a slide lecture – i.e. of something documentary, didactic, enlightening. For 15 years now, the artist has owned a slide case that she found in the garbage. It is entitled Nude bathing on the beach at El-Alamein. The man who took the photographs depicted his partner naked in various erotic poses by the sea. The character of the photos suggests that they could have been taken in the 1960s. But El-Alamein in Egypt had also been the scene of war; battles took place between the British 8th Army and German-Italian tank regiments during the African campaign here in 1942. The artist superimposes a private story and world history. Was the hobby photographer already here as a soldier? The artist knows that he not only archived his picture material obsessively but also continually transferred it onto the latest media – he has re-photographed Super 8 and diverse video formats. These processes of translation are also central to Tatiana Lecomte’s work, and analogue repro-photography is an important technique for her: she re-photographs his images, selecting different sections in places and zooming in on various details. She researches in books, taking photos of maps and historical images of the wartime battles from them. Together with images from the artist’s archive, which enable her to include herself in Positions at El-Alamein, the basis emerges for an associative but nonetheless meticulously chosen chain of images. Here, the gesture of pointing is made obvious by the fact that every photograph is held at the bottom right-hand corner. This is reminiscent of turning pages, and so the artist creates both the suggestion of a photo album and a greater involvement on the part of the viewer. We are shown that something is being shown. As a result, the images are rather like evidence, suggesting considerable truth content.

In “Nichts als die Wahrheit” (Nothing but the Truth), Texte zur Kunst, No. 51, Karin Gludovatz speculates: “Images are objects of memory and, perfiduously, they serve to evoke pleasant events just as we expect them to prevent the repetition of terrible occurrences due to their mnemotechnical function. In addition, a quality of special evidence is attributed to the documentary image – regardless of these dialectics – when writing both private and public history. Images as contemporary witnesses?”[2]

Tatiana Lecomte does not adopt a direct standpoint in either slide installation. She stays within an interim sphere, constructing a narration that makes it possible to experience the power of images subtly and thus making a deep impression. “Although we know better, photography still continues to represent reality, it confronts the viewer with facts. It is an assertion by the photographer. Sometimes this thesis is disguised as narrative, sometimes it is obviously fiction. The photographer can be involved more or less personally, telling a story or leaving the viewer to create his own associations and connections.”[3] This also applies to Tatiana Lecomte; but she immediately thinks of the utilization, multiple reproduction, validity and diverse purposes of the images – making all of this into the content of her work.

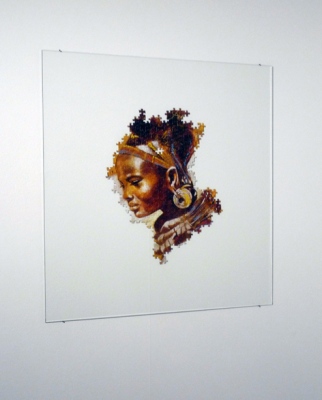

At the end of the exhibition, the focus returns to Africa. Taking a portrait from a 1000-piece puzzle issued by a well-known toy manufacturer that shows an “African Beauty” - a young black woman with traditional body decoration –, Tatiana Lecomte has assembled one section, laminating it and putting it behind glass. The incomplete puzzle with its gaps makes the portrait of the African woman seem rather like a mosaic. The “museum” presentation evokes the impression that it has slipped out of time, thus becoming eternally valid. Does this reproduce a cliché?

1 Roswitha Muttenthaler, Regina Wonisch, Gesten des Zeigens. Zur Repräsentation von Gender und Race in Ausstellungen, Bielefeld 2006, S.13f

2 Karin Gludowatz, Grauwerte, Ein Projekt von Klub Zwei zum Gebrauch historischer Dokumentarfotografie, in: Texte zur Kunst, September 2003, 13. Jahrgang, Heft 51, Nichts als die Wahrheit, S. 59

3 Gabriele Wagner, "Eigentlich sind es so gesehen reine Bilder, fast schon gegenstandslos ... ", in: David Steinbacher, Plenarsäle, Wörgl, 2012, S.12